Up in the foothills, only 20 minutes from Denver, there's a famous natural landmark where dinosaurs have a story to tell. It’s the perfect family-friendly excursion where learning is fun

During the Cretaceous Period, or 145 million to 66 million years ago, Denver was beachfront property. Back then, the Western Interior Seaway divided North America into two land masses, the weather was warm and polar icecaps didn’t exist.

West of the city in what is now unincorporated Jefferson County, Dinosaur Ridge was prime real estate during this era of the inland sea.

Things changed as eons passed. The sea receded, and more than a mile’s worth of mud accumulated around Dinosaur Ridge, obscuring all evidence of the namesake titans that once frolicked at water’s edge here. The earth tilted upward and exposed much older geology on the ridge’s west side.

Uncovering the Tracks

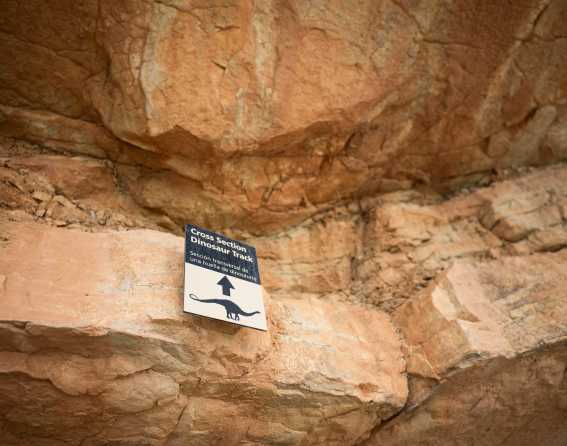

In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps uncovered the dinosaurs’ old stomping grounds while building a road meant to connect the city and Red Rocks Park & Amphitheatre, another CCC project. And stomping is literal here: There are more than 250 distinct dinosaur tracks at the main site of the National Natural Landmark from three species, along with scratches from crocodilians.

“This is the number one track site in North America,” says Amanda Rea, camp director and collections manager for Friends of Dinosaur Ridge, the nonprofit that manages the site and its public tours. Number three is Triceratops Trail in Golden, which is also run by Friends of Dinosaur Ridge.

The late Friends of Dinosaur Ridge co-founder Martin Lockley “was a huge ichnologist,” says Rea. “An ichnologist is someone who studies trace fossils — tracks and eggs and things that were not part of the body.... It can show the lives of dinosaurs, not just their deaths.”

A shallow, round impression at the main track site is evidence of the need to protect these tracks.

“Rumor has it, it ended up in a dorm at a certain Colorado college,” laughs Rea, noting that someone later returned it. “If you don’t educate people about these sites, they don’t understand why you shouldn’t take them.... This is a non-renewable resource.”

There are several more sights to see as you crest the ridge. Ripple marks left by the long-gone sea have been preserved for posterity in the stone on the way to the top, places where microbial mats were torn asunder and the tidal movement shaped the sand left exposed.

Descending on the west side, the uplift has revealed older tracks from the sauropods of the Jurassic Period left more than 150 million years ago at an area called the Bulges.

“We’re too old for T-Rex, but we have a T-Rex ancestor called allosaurus,” says Rea, noting that Triceratops Trail includes T-Rex tracks.

Just down the road at the aptly named Bone Bed, look for the shiny reddish material embedded in the stone. It’s the exposed edge of a dinosaur bone that’s taken on color from iron and other minerals. Geologist Arthur Lakes was the first person to examine stegosaurus material here back in the late 1800s.

Other Things to See and Do

Bus tours are available every day aside from major holidays from the main visitor center on the east side of the ridge, along with downloadable audio tours and walking tours during the non-winter months. Pedestrians and bicyclists can access Dinosaur Ridge for free on a 1.1-mile paved trail that gains 300 feet to the top.

Some people like to come here for exercise and the stellar views of the mountains, Red Rocks and Denver’s cityscape unspooling to the east. The Dakota Ridge Hiking Trail’s southern terminus is near a lookout near the top of the ridge; hike north and you’ll soon enter Matthews/Winters Park with 14 miles of trails.

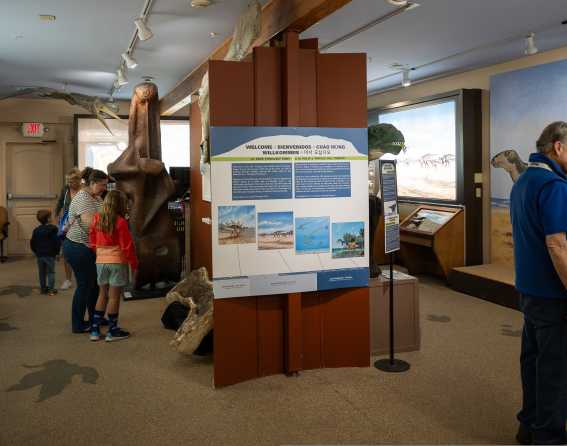

Adjacent to the visitor center and gift shop where the tours depart, there’s also an Exhibit Hall detailing the geological and ecological evolution of the surrounding landscape, and plenty of fun diversions for kids. They can dig for shells to keep in the Seaway Fossil Box and pose for selfies with the numerous dinosaur statues.

Having such a notable paleontological site right on the outskirts of a major metro area is something of an anomaly.

“It’s a must-see,” says Kristen Kidd, Friends of Dinosaur Ridge director of marketing and development. “Every city has a zoo or a museum. Not every place has such an accessible site where you can see dinosaur footprints in the stone where they were made.”

Related Content

Only in Denver: Fossil Prep Lab

- 5 minute read

Denver Museum of Nature & Science has a little something for everyone, from gemstones, to Martian dust devils, to wildlife and even some…

Best Kid-Friendly Hikes Near Denver

- 3 minute read

Hundreds of exciting adventures for the whole family can be found near the Denver metro area. If you’re planning a hike with young ones…

Only in Denver: Mordecai Children’s Garden at Denver Botanic Gardens

- 2 minute read

What does one do with an empty, one-acre parking garage rooftop? If you’re Denver Botanic Gardens, you cover it, edge to edge, in a living…

Best Birdwatching Spots Near Denver

- 2 minute read

Birding can be a valuable introduction to nature and ecology for children. Birds are not as elusive as other wildlife and can be viewed safely…